Still Burning

I have not watched the movie Mississippi Burning. I am not a cinephile. It is not that I dislike movies. I do not often have 2-3 hours to sit and watch one. I learned a lot about the movie when I listened to a podcast from The Experiment about the events portrayed in Mississippi Burning.

This podcast inspired me to do some research and engage in a thought experiment about white supremacy and family values. I outlined some of my research and summarized that thought experiment in the following paragraphs.

Click the link below to view a video from The American Experience about this incident.

The Research

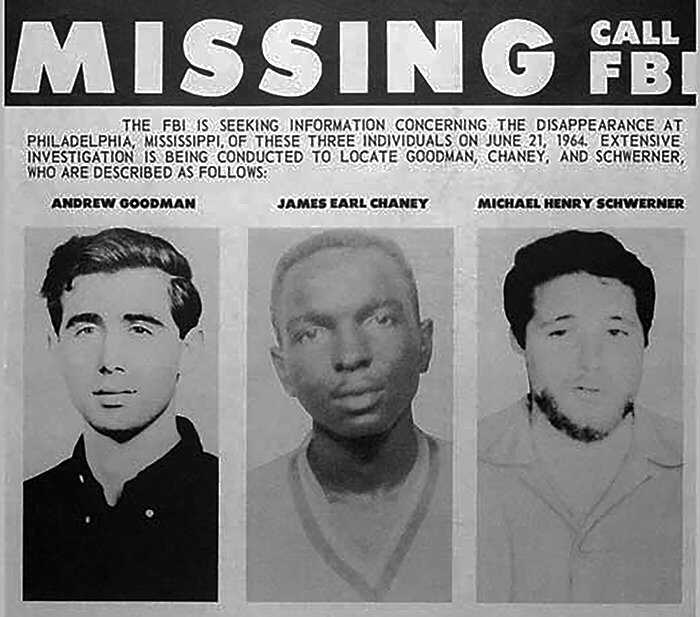

James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner, three civil rights workers engaged in the activities of Freedom Summer, were arrested for allegedly speeding in Philadelphia, Mississippi, in June 1964. They were held for a time and eventually released from jail after dark. On their way out of town, local clan members tried to run them off the road. Chase ensued, and a sheriff’s deputy eventually pulled over the three men. The deputy took them into custody. However, rather than take them back to the jail, the deputy delivered them to the clan members, who brutally murdered them. The bodies of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner were found 44 days later, buried in rural Neshoba County, Mississippi.

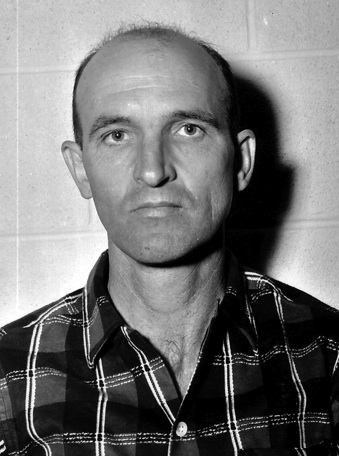

Edgar Ray Killen, the man ultimately held responsible for the murders of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner in 2005 (yes, 40 years after he committed the crime), was 39 in June 1964. Killen was an ordained Baptist minister and a Kleagle (clan recruiter and organizer) for the KKK. Killen was of my grandfather’s generation. In 2014, the Clarion Ledger and NBC News reported that Killen was still a segregationist who did not believe in racial equality. The Southern Poverty Law Center reported that Killen was reprimanded 17 times for racist behavior while imprisoned.

While a mob was responsible for the brutal murders of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner, Killen was the only one to face murder charges. Nineteen men, including Killen, were indicted on federal charges of violating civil rights laws in 1967. However, only seven were convicted, and none served more than six years for their crimes. Killen was not one of the seven convicted.

ABOVE: FBI Missing Poster for Goodman, Chaney, and Schwerner. Obtained from the FBI.

BELOW: 1964 Booking Photo of Edgar Ray Killen. Obtained from Wikipedia.

Lindon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965 into law on August 6, 1965, a year after the events of Mississippi Burning. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 outlawed the Jim Crow voting practices many southern states adopted after the Civil War. It required certain districts obtain preclearance to change their voting laws. This prevented them from passing new voting laws that targeted people of color. This part of the Voting Rights Act was later ruled unconstitutional by Shelby v Holder in 2013, less than 50 years after the Voting Rights act was signed. This meant that districts with a history of voter discrimination based on race no longer had preclearance oversite.

The horrific murders of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner happened less than 60 years ago. The Supreme Court overturned the legislation designed to prevent voter disenfranchisement less than ten years ago. Yet, according to the ACLU, more than 400 anti-voter bills have been introduced in recent years. These bills “disproportionately impact people of color, students, the elderly, and people with disabilities.” The Voting Rights Act of 1965 may have prevented these bills because of the additional oversight it required.

The Thought Experiment

I began thinking about this in terms of my life and my family. Is it fair to think the white supremacy and racist ideas that brought about the brutal murders of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner in June 1964 are gone? So I began a thought experiment using my family and upbringing for comparison.

Every family has a set of values they hold dear. All families have these values. The value could be a specific religious belief, to always help others, even white supremacy. I never said the values were good, just that they were values. We can debate the good and bad of values at another time.

My mom was 17 in 1964. My grandfather was 48. I was born in 1980, less than 1 generation removed from this crime.

My family values education. My family has passed down this value for at least five generations. My great great grandpa Koetting (b. 1855 d. 1930) made sure his daughters (one of whom was my great grandma, Anna, b. 1887 d. 1968) went to school through 8th grade. At the time, third grade was the standard for girls. Long enough that they could read, write, and do basic math – the skills necessary to run a household. My great great grandpa wanted his daughters to have a better education than the basics.

My grandpa (b. 1916 d. 1993) did not graduate high school, partly because he had to take over the family business in the early 1930s after his grandpa (my great great grandpa Koetting) died, leaving behind a lumber business that needed tending.

My grandma’s side of the family valued education just as strongly as my grandpa’s. My grandma (b. 1918 d. 2014) graduated high school and got a good job at the local bank. She was good with numbers. Both my grandparents read the newspaper daily and sent their four children to the local Catholic school. Three of their children went on to get college degrees. None of them stopped learning. My grandparents instilled the value of education in their kids that was passed to them from previous generations.

My grandpa paid my cousin and I (their only two grandchildren) for each A we received on our report cards. An incentive to encourage us to study. Our family expected us to apply ourselves. I went to Catholic school too. My grandma asked me each day after school if I had any “lessons” to complete. She was checking to see if I needed to do any homework. My mom had a library in her home and I pulled books off the shelves to read. My mom never told me a book was off-limits. I was fascinated by her set of Man, Myth, and Magic books, which illustrated cultures of the world in vivid photographs. I reviewed her copies of The Joy of Sex and More Joy when I hit adolescence. I found Rosemary’s Baby on her bookshelves when I was 14 and spent a week reading a horrifying and captivating story that summer. I read Shakespeare from books printed at the turn of the 20th century. She read to me as a child and always encouraged reading as I grew up.

My cousin is married now and has a ten-year-old son. He and his wife are teaching their son the importance of education. They send him to Catholic school. Their son loves to read and generally seems to enjoy learning.

He is at least the sixth generation of my family who has been taught to value education. I am sure this value has deeper roots than six generations; however, I only know enough family history to speak to this timeframe. If my family has passed this value through more than a handful of generations spanning about 170 years, then the values of other families can have similar staying power. It is possible that the values of the other men who murdered those civil rights workers in Philadelphia, Mississippi, in June 1964 passed their white supremacist and racist values down to their children and grandchildren. Their grandchildren would be of my generation.

Killen had no children, so (thankfully) he could not pass his white supremacist and racist values down the family line.

The Conclusion

The Civil Rights movement of the 1960s occurred as the first third of the Baby Boomer generation came of age. Their children were born in the 1970s and 80s. Mine is the first generation born after the Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and 1968 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Unfortunately, the beliefs that facilitated the need for this legislation are not dead in the US and will likely be passed down for generations in some families until we as a society snuff it out.

It is not easy to change the programming of your upbringing. Ask anyone who has tried. If you live in an environment where the only message you hear is that a certain group of people is bad, it is hard to go against the societal norm. We can only do better when we know better. Unfortunately, some families and areas of our country still hold white supremacist and racist ideas as valuable and continue to pass those ideas down to future generations.

If the last seven years have taught me anything, it’s that white supremacy and racism are still alive in the U.S.

The racism that caused the story of Mississippi Burning is still alive. It is as deeply ingrained a value in some families as education is in mine. For all of the strides the United States has made toward equal rights regardless of race, skin color, or gender, we have ideas about these concepts that families have taught for generations. Unfortunately, this work is far from over.

We cannot act like it is.

References

ACLU. (2021, August 17). Block the Vote: How Politicians are Trying to Block Voters from the Ballot Box. ACLU. Retrieved on December 29, 2022, from https://www.aclu.org/news/civil-liberties/block-the-vote-voter-suppression-in-2020

Barrouquere, B. (2018, March 21). The last days of a Klansman: Edgar Ray Killen remained a defiant racist in prison until the end. Southern Poverty Law Center. Retrieved on December 29, 2022, from https://www.splcenter.org/hatewatch/2018/03/21/last-days-klansman-edgar-ray-killen-remained-defiant-racist-prison-until-end

Brennan Center for Justice. (2018, August 18). Shelby Country v Holder. Brennan Center for Justice. Retrieved on December 29, 2022, from https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/court-cases/shelby-county-v-holder

Elliot, J. (2014, Dec. 22). Interview: Killen Stays silent about 1964 civil-rights deaths. Clarion Ledger. Retrieved on December 29, 2022, from https://www.clarionledger.com/story/news/local/2014/12/22/convict-civil-rights-deaths-confess/20778207/

Linder, D.O. (2022). Mississippi Burning Trial (1967). Famous Trials. Retrieved on December 29, 2022, from https://famous-trials.com/mississippi-burningtrial

Longoria, J. (Host). (2022, May 19.) Fighting to Remember Mississippi Burning [Audio podcast episode]. In The Experiment. WNYC Studios. https://www.wnycstudios.org/podcasts/experiment/episodes/ko-bragg-freedom-summer-murders-mt-zion-church

The National Archives (2022, February 8). Civil Rights Act (1964). The National Archives. Retrieved on December 29, 2022, from https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/voting-rights-act#:~:text=This act was signed into,as a prerequisite to voting.

The National Archives (2022, February 8). Voting Rights Act (1965). The National Archives. Retrieved on December 29, 2022, from https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/voting-rights-act#:~:text=This act was signed into,as a prerequisite to voting.

NBC News. (2018, January 12). Edgar Ray Killen, convicted of 1964 Mississippi Burning Killings, dies at 92. NBC News. Retrieved on December 29, 2022, from https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/edgar-ray-killen-convicted-1964-mississippi-burning-killings-dies-92-n837171

PBS. (2020, October 15). Mississippi Justice by American Experience. [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/FFEsQwjTbJc

Shelby County v. Holder. (n.d.). Oyez. Retrieved December 30, 2022, from https://www.oyez.org/cases/2012/12-96